|

|---|

| Newtons canon. |

A black hole is simply an object from which light can’t escape. If particles of light (photons) cannot escape the surface of the object, then we can’t see the object - hence the name.

|

|---|

| A black hole. |

They can be formed from the gravitational collapse of massive stars but are also of interest in their own right, independently of how they were formed.

|

|---|

| Life cycle of a star. |

Far from being hungry beasts devouring everything in their vicinity as shown in popular culture, we now believe certain (supermassive) black holes actually drive the evolution of galaxies.

|

|---|

| The first ever image of a black hole at the heart of the M87 galaxy taken in April 2019. |

At the centre of our own galaxy, the milky way, the supermassive black hole is called Sagitarrius A* and has a mass of 2.6 million times the mass of our sun.

|

|---|

| Orbit of stars around the central black hole, Sagittarius A.* |

|

|---|

| The second ever image of a black hole, Sagittarius A, at the heart of the our galaxy taken in May 2022. |

The first person to come up with the idea of a black hole was John Mitchell in 1783, followed (independently) by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1796. These prototypical black objects, called ‘dark stars’, were considered from the point of view of Newton’s law of motion and gravitation.

In particular, Mitchell calculated that when the escape velocity at the surface of a star was equal to or greater than lightspeed, the generated light would be gravitationally trapped, so that the star would not be visible to a distant astronomer.

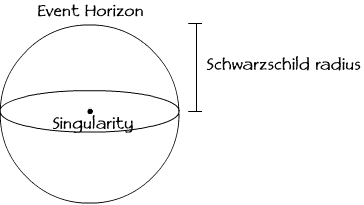

The event horizon is the boundary of this region, also known as the ‘point of no return’ because once you go past this point it is impossible to turn back.

|

|---|

| The black hole region. |

Black holes also arise as solutions in Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The first such solution was found by Karl Schwarzchild in 1916 and called the ‘Schwarzchild solution’. It was originally formulated in order to describe the gravitational field of the solar system, and to understand the motion of objects passing through this field, but the idea of a black hole remained as an intriguing possibility.

The first black hole was discovered in 1964 called Cygnus X1 and it is estimated to have a mass of about 14.8 times the mass of the sun.

|

|---|

| Cygnus X1 is a galactic X-ray source discovered during a rocket flight. |

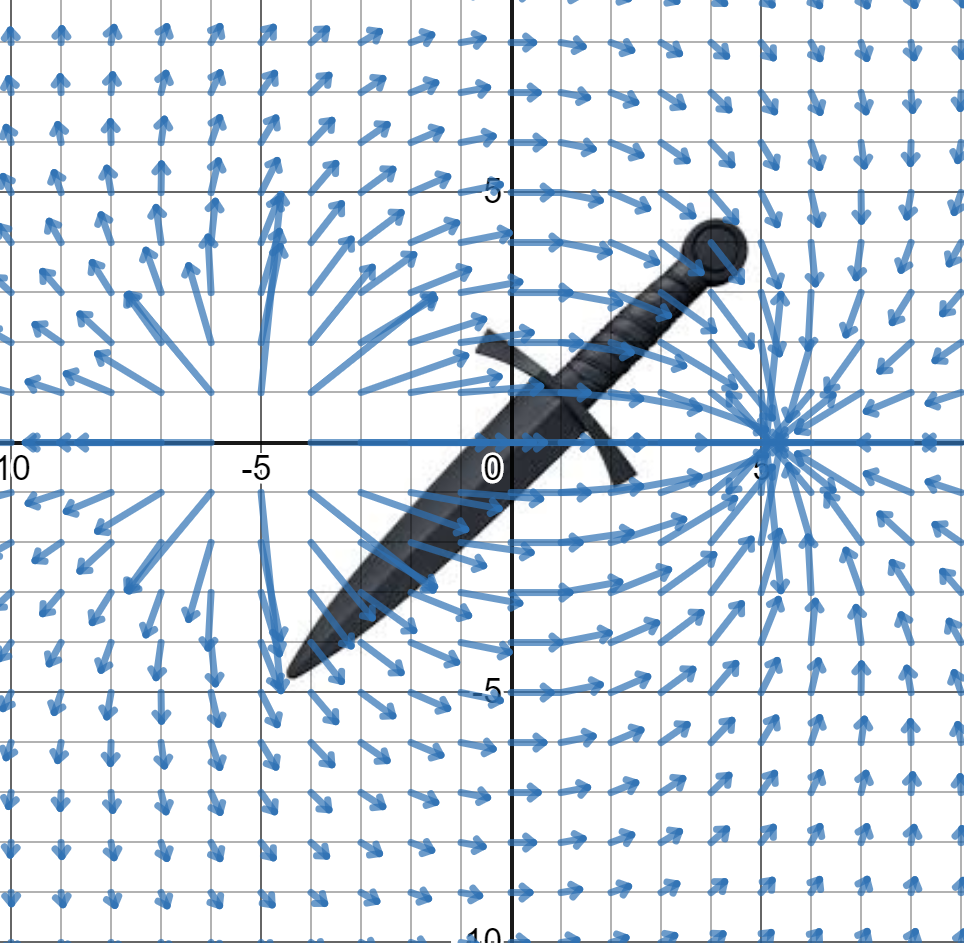

The first person to come up with the idea of a black hole was John Mitchell in 1783, followed (independently) by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1796. These prototypical black objects, called ‘dark stars’, were considered from the point of view of Newton’s law of motion and gravitation. In particular, Mitchell calculated that when the escape velocity at the surface of a star was equal to or greater than lightspeed, the generated light would be gravitationally trapped, so that the star would not be visible to a distant astronomer. The event horizon is the boundary of this region, also known as the ‘point of no return’ because once you go past this point it is impossible to turn back. To see this, consider an object of mass \(m\) and a spherically symmetric body of mass \(M\) and radius \(R\). The total energy is, \begin{eqnarray} \label{te} E = \frac{1}{2}m v^2 - \frac{G m M}{r} \ , \end{eqnarray} where \(r\) is the distance from the centre of mass of the body to the object. We can also write this as \(r = R + h\), where \(h\) is the distance from the surface of the body to the object, but the region we will consider is at \(r \geq R\) or \(h \geq 0\). An object that makes it to \(r \rightarrow \infty\) will have \(E \geq 0\) as the kinetic energy will dominate for large \(r\). This implies, \begin{eqnarray} v \geq v_e(r) \equiv \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r}} \ , \end{eqnarray} where \(v_e(r)\) is the escape velocity, which is the lowest velocity which an object must have in order to escape the gravitational attraction from a spherical body of mass \(M\) at a given distance \(r\). By energy conservation, we have at the surface of the body (\(r=R\)), \begin{eqnarray} v \geq v_{e}(R) = \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{R}} \ . \end{eqnarray} This is independent of the mass of the escaping object, by the equivalence of inertial and gravitational masses. Now the escape velocity at the surface is greater than the speed of light, \(v_e (R) > c\) if \begin{eqnarray} R < r_s \equiv \frac{2GM}{c^2} \ . \end{eqnarray} The radius \(r_s\) is now understood in terms of the Schwarzschild radius. The surface \(r = r_s \) acts as an ‘‘event horizon” if the body fits inside this radius. Of course, there is nothing particularly special about the speed of light \(c\) in the Newtonian (non-relativistic) gravity. Objects in principle could move faster than \(c\) which means that they may always escape the would-be black hole. Moreover, a photon emitted from such an object does leave the object, although it would eventually fall back in. Thus there are no real black holes (a body from which nothing can escape) in Newton’s gravity.

As we now understand photons to be massless, so the naive analysis described above is not physically realistic. However, it is still interesting to consider such objects as a starting point. The consideration of such ‘‘dark stars” raised the intriguing possibility that the universe may contain a large number of massive objects which cannot be observed directly. This principle turns out to be remarkably close to our current understanding of cosmology. However, the accurate description of a black hole has to be general relativistic.

Isaac Newton was to be overturned by Albert Einstein with his special theory of relativity in 1905, which showed that the speed of light was constant in any reference frame and then his general theory of relativity in 1915 which describes gravity as the curvature of space-time \cite{einsteingr}; \begin{eqnarray} R_{\mu \nu} - \frac{1}{2}R g_{\mu \nu} = 8 \pi G T_{\mu \nu} \ . \end{eqnarray} The theory relates the metric tensor \(g_{\mu \nu}\), which defines a spacetime geometry, with a source of gravity that is associated with mass or energy and \(R_{\mu \nu}\) is the Ricci tensor. Black holes arise in general relativity as a consequence of the solution to the Einstein field equations found by Karl Schwarzschild in 1916. Although the Schwarzschild solution was originally formulated in order to describe the gravitational field of the solar system, and to understand the motion of objects passing through this field, the idea of a black hole remained as an intriguing possibility. Einstein himself thought that these solutions were simply a mathematical curiosity and not physically relevant. In fact, in 1939 Einstein tried to show that stars cannot collapse under gravity by assuming matter cannot be compressed beyond a certain point.

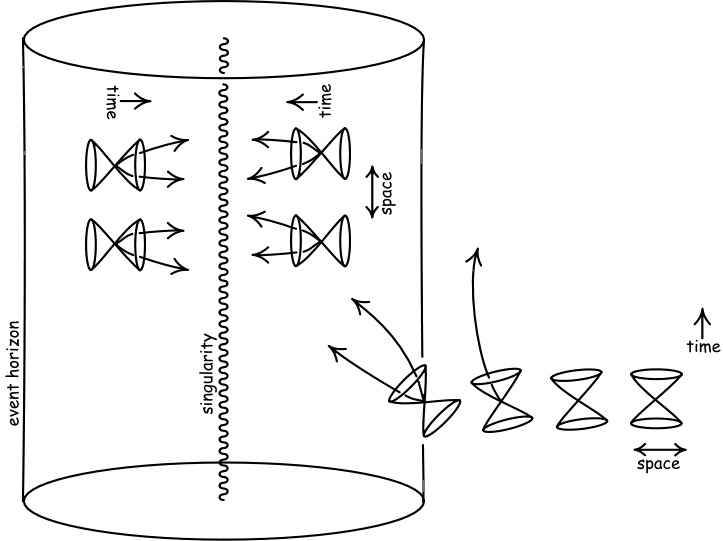

The Schwarzschild radius can also be realized by considering the Schwarzschild solution in general relativity i.e any non-rotating, non-charged spherically-symmetric body that is smaller than its Schwarzschild radius forms a black hole. This idea was first promoted by David Finkelstein in 1958 who theorised that the Schwarzschild radius of a black hole is a causality barrier: an event horizon. The Schwarzschild solution is an exact solution and was found within only a few months of the publication of Einstein’s field equations. Instead of dealing only with weak-field corrections to Newtonian gravity, full nonlinear features of the theory could be studied, most notably gravitational collapse and singularity formation. The Schwarzschild metric written in Schwarzschild Coordinates \((t, r, \theta, \varphi)\) is given by, \begin{eqnarray} ds^2 = -f(r) c^2 dt^2 + f(r)^{-1} dr^2 + r^2 \left(d\theta^2 + \sin^2\theta \, d\varphi^2\right) \ , \end{eqnarray} where \(f(r) = 1-r_s / r\). In this form, the metric has a coordinate singularity at \(r=r_s\) which is removable upon an appropriate change of coordinates. The Kretschmann scalar for this metric elucidates the fact that the singularity at \(r=0\) cannot be removed by a coordinate transformation, \begin{eqnarray} R_{\mu \nu, \rho \sigma}R^{\mu \nu, \rho \sigma} = \frac{4G^2M^2}{c^4 r^6} \ , \end{eqnarray} where \(R_{\mu \nu, \rho \sigma}\) is the Riemann tensor. A more accurate general relativistic description of the event horizon is that within this horizon all light-like paths and hence all paths in the forward light cones of particles within the horizon are warped as to fall farther into the hole.

My thesis was on dynamical symmetry enhancement of black hole horizons. In particular, I studied black holes in the context of quantum gravity and I was able to prove certain mathematical properties in a much more general and unified way than previous work on the subject.

In order to explain this, first let me talk about a few concepts.

Symmetry is an important concept in fundamental physics, often implemented using the mathematics of group theory and Lie algebras. A symmetry transformation is one that leaves all measurable quantities intact.

|

|---|

| The Lie group E8. |

|

|---|

| A visual representation of a Calabi-Yau manifold. |

The geometry of a black hole is encoded in the metric tensor, which captures the geometric and causal structure of space-time – which is used to define notions such as time, distance, volume etc.

The symmetries of the metric tensor are captured by something called a Killing vector, the number of which tells you the amount of symmetry you have.

It was shown by Stephen Hawking that the event horizon of a black hole in 4-dimensional spacetime must have spherical topology.

|

|---|

| Penrose diagram of a collapsing star. |

|

|---|

| Light cones tipping near a black hole. |

|

|---|

| The Schwarzschild waterfall. |

|

|---|

| Event horizon of a black hole enclosing a singularity. |

The near-horizon geometry of a black hole is what we see when we zoom in right at the event horizon of a black hole, which usually has a more constrained geometry with more killing vectors, which is what is known as symmetry enhancement. This zooming in is called the near horizon limit.

The spherical topology of the event horizon is no longer true for black holes in higher dimensions, where most proposed unified theories of nature or quantum gravity are defined. This means we have to re-examine the shape for black holes in these theories as previously established results such as the uniqueness theorem no longer hold.

The proof the no-hair theorem relies on the Gauss-Bonnet theorem applied to the 2-manifold spatial horizon section and therefore does not generalize to higher dimensions. Thus for dimensions \(D>4\), uniqueness theorems for asymptotically flat black holes lose their validity. Indeed, the first example of how the classical uniqueness theorems break down in higher dimensions is given by the five-dimensional black ring solution \cite{Emparan:2001wn, BR1}. There exist black ring solutions with the same asymptotic conserved charges as BMPV black holes, but with a different horizon topology. Even more exotic solutions in five dimensions are now known to exist, such as the solutions obtained in \cite{Horowitz:2017fyg}, describing asymptotically flat black holes which possess a non-trivial topological structure outside the event horizon, but whose near-horizon geometry is the same as that of the BMPV solution.

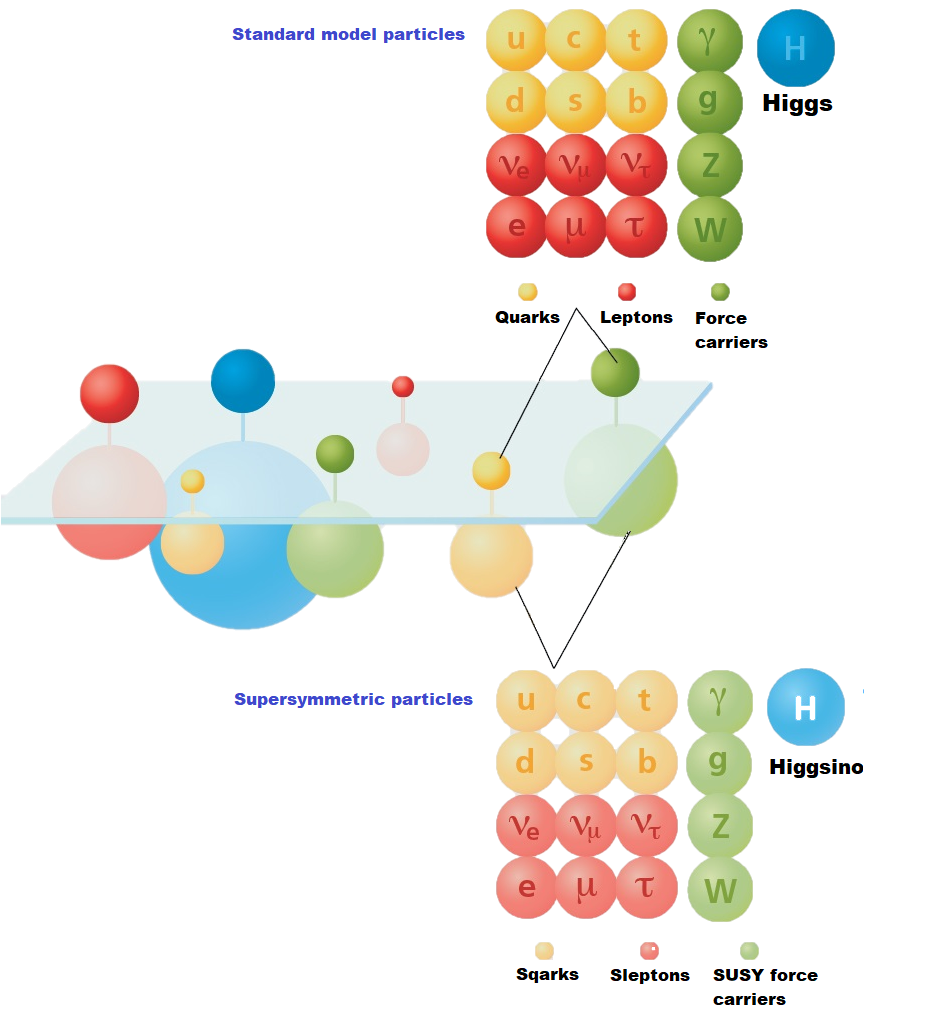

Supersymmetry is a concept that introduces a symmetry between bosons and fermions. Similar to symmetry, the number of supersymmetries is captured by something called a Killing spinor, and the number of Killing spinors tells you how much supersymmetry is realized for a given solution. The killing spinors also imply the field equations for any given theory, but are usually easier to solve as they are first-order differential equations while the field equations are second-order.

|

|---|

| The Standard Model and Supersymmetry. |

We were able to show that black holes in particular supergravity theories undergo symmetry enhancement, and for these theories the number of supersymmetries are always an even number. We were also able to investigate other properties of the near-horizon geometry and eliminate certain solutions. The work was done by analysing and solving certain differential equations.

Black hole research is at the forefront of modern physics because much about black holes is still unknown. Currently, the best two theories we have that describe the known universe are the Standard Model of particle physics (a quantum field theory) and general relativity (a classical field theory). Most of the time these two theories do not talk to each other, with the exception of two arenas: the singularity before the Big Bang and the singularity formed within a black hole. The singularity is a point of infinite density and thus the physical description necessarily requires quantum gravity. Indeed Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking also showed 48 years ago that, according to general relativity, any object that collapses to form a black hole will go on to collapse to a singularity inside the black hole \cite{penrose}. This means that there are strong gravitational effects on arbitrarily short distance scales inside a black hole and such short distance scales, we certainly need to use a quantum theory to describe the collapsing matter.

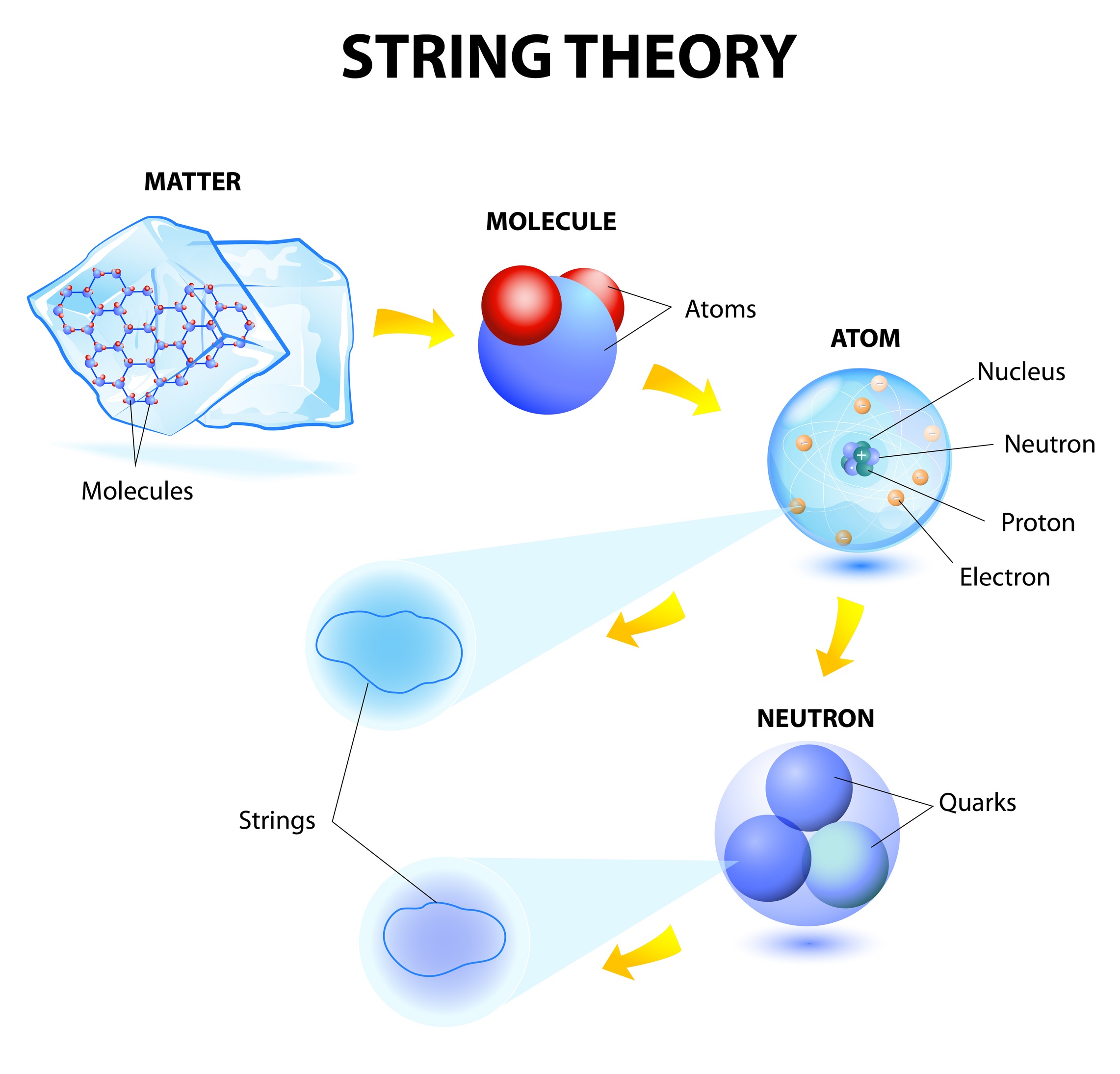

General relativity is not capable of describing what happens near a singularity and if one tries to quantize gravity \textit{naively}, we find divergences that we can’t cancel because gravity is non-renormalizable\footnote{In particular, the number of counterterms in the Lagrangian, required to cancel the divergences is infinite and thus the process of renormalization fails.} \cite{goroff}. String theory is a broad and varied subject that attempts to remedy this and to address a number of deep questions of fundamental physics. It has been applied to a variety of problems in black hole physics, early universe cosmology, nuclear physics, and condensed matter physics, and it has stimulated a number of major developments in pure mathematics. Because string theory potentially provides a unified description of gravity and particle physics, it is a candidate for a theory of everything, a self-contained mathematical model that describes all fundamental forces and forms of matter.

In the currently accepted models of stellar evolution, black holes are thought to arise when massive stars undergo gravitational collapse, and many galaxies are thought to contain supermassive black holes at their centers. Black holes are also important for theoretical reasons, as they present profound challenges for theorists attempting to understand the quantum aspects of gravity. String theory has proved to be an important tool for investigating the theoretical properties of black holes because it provides a framework in which theorists can study their thermodynamics, aided in particular by properties such as supersymmetry.